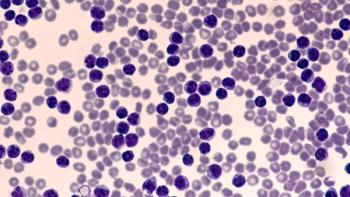

Treatment Selection Strategies for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

Anthony Perissinotti and Kirollos Hanna discuss considerations for selecting treatment regimens in chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Episodes in this series

Kirollos Hanna, PharmD, BCPS, BCOP: We’ve discussed tons of information. We’ve talked about BCL2 BTK [Bruton tyrosine kinase]. We’ve talked about finite treatment durations. We’ve talked about long-term efficacy from BTK and BTK plus anti-CD20. Clearly, this landscape is becoming extremely crowded and the treatment algorithms are becoming more complicated. Walk us through treatment selection strategies for a patient with CLL [chronic lymphocytic leukemia].

Anthony Perissinotti, PharmD, BCOP: The unbiased opinion is to throw venetoclax and obinutuzumab into a hat with ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib, and pick 1 out. Honestly, that’s the right therapy for the patient—these are all fantastic options. My preference is to use venetoclax with obinutuzumab. The reason is that you have a fixed duration. You’re going to treat these patients in the frontline setting for only 1 year. Based on CLL14, the majority of your patients 4 years later are still going to be off therapy. No. 1, patients are going to be off therapy. They’re not going to have adverse effects from a therapy they’re not on. No. 2 is the cost of therapy. There was an analysis published that looked at a variety of regimens: ibrutinib-based regimen vs FCR [fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab] vs chlorambucil-obinutuzumab vs venetoclax with obinutuzumab, so the CLL14 study. On a 3-year horizon, you’re looking at about $350,000 for venetoclax-obinutuzumab, which sounds like a lot until you go and look at the BTK inhibitors. You’re looking at $500,000 to $600,000 over a 3-year horizon for most patients.

Based on RESONATE-2 data presented at ASH [American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting], roughly 60% of patients are still on therapy at 7 years. With a horizon of 7 years, you’re looking at millions of dollars. From a cost perspective, the majority of patients should get a finite therapy of venetoclax-obinutuzumab. That being said, the elephant in the room is COVID-19. None of us wants to bring our patients into our infusion centers to receive obinutuzumab. Most of us are trying to avoid an anti-CD20 monoclonal [antibody] because of vaccine responses, so it’s very appealing to write a prescription for a BTK inhibitor, send the patient home, and do virtual visits. That’s the challenge with COVID-19. We have swayed toward using single-agent oral therapy because of it.

Other patients for whom I’d consider a BTK inhibitor are those with TP53 mutations. The [University of Texas] MD Anderson [Cancer Center] presented its data at ASH. It was about 6 years of follow-up, and 60% of patients are progression-free despite having a TP53 mutation. This is very similar to RESONATE-2. Essentially, your TP53 patients are doing as good as any other patient with CLL if they’re treated with a BTK inhibitor. A TP53 mutation sways toward a BTK inhibitor for me, as opposed to venetoclax.

Then the question is which BTK inhibitor do you choose? We’ve been using ibrutinib for almost a decade, so we have a lot of personal experience with it. Most of our patients were still using ibrutinib. If there’s any patient we’re worried about who has comorbidities or cardiovascular disease, and we’re worried about long-term complications, if this patient does get A-fib [atrial fibrillation] or hypertension, what’s that going to mean for their long-term outcome? We’re swaying toward using our second-generation [BTK inhibitors]. As I said, some institutions have abandoned ibrutinib and are going on because the data support that. The data support that BTK inhibitors or second-generation [BTKs] are better tolerated.

What about at your center in the front line? Anything? I don’t want to give my own bias, but that’s my interpretation of the literature. That’s what I’m looking at for patients. Being off therapy and the cost of therapy are 2 of the most important things, from my perspective, [along with] your ability to manage the toxicities. If you’re comfortable preventing or managing the toxicities, I don’t think ibrutinib is a bad option. But if you’re uncomfortable, and you only treat a few [patients with] CLL per year, you probably should move on to second-generation [BTKs]. What are your thoughts?

Kirollos Hanna, PharmD, BCPS, BCOP: I totally agree with you, Dr Perissinotti. It’s really exciting. In CLL, we can almost say that our patients are going to succumb to older age or other comorbidities not related to their disease. We have numerous exciting options. But I’m in favor of what you’re saying and more in favor of finite treatment duration. You limit costs, you limit treatment exposure, you limit adverse event [AE] potential. We know from what we’ve learned that these patients can still respond to some of the therapies that we’ve already used in the finite approach vs telling someone you’re going to be on ibrutinib for 8, 9, 10 years. It poses a challenge.

That brings us into the bucket of some challenges we’re seeing in the CLL patient population, which will also help us segue into future perspectives of CLL. One challenge we’re seeing predominantly in CLL is that if you have a patient who’s double exposed, and you’ve exhausted your BTK and BCL2, what now? Do we go PI3K? Do we go chemoimmunotherapy? This is where we have some challenges with PI3Ks. We’re going to talk about some exciting things coming up, but PI3Ks are hard to tolerate, at least the ones that we have that have been FDA approved in CLL or more widely utilized, and they’ve really fallen out of favor.

We see a lot of immune-related adverse events or adverse events that [result from] immunotherapy, something like a pembrolizumab, for example. We see a lot of colitis, a lot of GI [gastrointestinal] involvement, and a lot of other AEs that many patients aren’t used to when they were on BCL2 or BTK. By this time, they’re older, they’re more frail, and they have more comorbidities, so chemoimmunotherapy is not a very good option for many of these patients. What do we do? Do we enroll them in a clinical trial looking at all the exciting approaches we’ve seen? Is 1 patient more appropriate than another? It becomes very challenging. But in clinical practice, I’m not seeing many patients for whom I think about a third-line setting. That’s really exciting to say about CLL in this day and age.

Transcript edited for clarity.

Newsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.