- March 2018 HPV Vaccination Supplement

- Volume 84

- Issue 3

Year-Round Solutions Beyond the Influenza Season

As the margin between acquisition cost and sales price continues to narrow for traditional community pharmacy medication dispensing, many pharmacies are increasingly turning to service-based opportunities to improve their profitability.

As the margin between acquisition cost and sales price continues to narrow for traditional community pharmacy medication dispensing, many pharmacies are increasingly turning to service-based opportunities to improve their profitability. The cornerstone of many pharmacy service programs offered beyond medication dispensing has traditionally been found in pharmacy vaccination programs.

The business case for vaccines within daily pharmacy practice has been compelling for many community pharmacies.1 The margins are good, the service itself is both relatively quick and directly connected to a billable product, it fits well into conventional pharmacy workflows, and pharmacists are excellently positioned and well-trained to deliver the service. Nevertheless, most pharmacies are only capturing a fraction of vaccination opportunities within their panel of patients. Even for patients who are presenting specifically to receive a vaccine, pharmacists often miss the chance to close additional vaccine gaps when the patient presents.

As an example of how to increase overall non-influenza vaccinations year-round, this article examines some best practices associated with the 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) recombinant vaccine (Gardasil 9, Merck & Company).

Know Your Epidemiology

Pharmacists should have a strong familiarity with the basic epidemiology and background of any vaccine they administer. The ability to provide a clear and concise explanation for the importance of a vaccine in an important component for making a cogent case that the vaccine a pharmacist is recommending is indeed necessary for the patient, especially for non-influenza vaccinations.

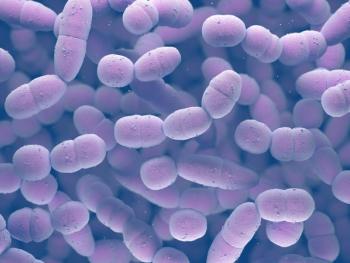

The HPV vaccine is used to prevent HPV, the single most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States. An estimated 80 million persons are infected, and an estimated 14 million new HPV infections occur every year among individuals 15 to 59 years of age. Roughly half of new infections occur among individuals 15 to 24 years of age, due to the fact that HPV infection is associated with the first few months to years of becoming sexually active. HPV infections have been strongly associated with a variety of cancers in both men and women, including cervical, vulvar, vaginal, penile, anal, and oropharyngeal cancers, hence the importance of its prevention.2-4 A majority of HPV-associated cancers are connected with infections of HPV 16 and 18, two of the strains covered in the 9-valent HPV vaccine.2 In the US, there are approximately 30,000 HPV-associated cases of cancer every year, of which 28,000 could have been prevented by the vaccine.2

Identifying Appropriate Patients

One of the most important aspects of making a strong recommendation is identifying appropriate patients to whom to make a recommendation. The need to directly incorporate a knowledge of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines and schedules issued by the Advisory Council for Immunization Practices (ACIP) into recommendations included in everyday workflows cannot be overemphasized. Simply printing the most current schedules and posting them in the pharmacy is not sufficient to allow for a pharmacist to make a recommendation to a patient; the information within the schedules needs to be constantly front of mind.

For pharmacists who struggle with maintaining an up-to-date knowledge of the somewhat complex ACIP schedules for children, adolescents, and adults, some technology vendors have incorporated tools that generate an ACIP schedule-based forecast for a given patient directly into pharmacy management systems and clinical platforms. Although these tools can be especially helpful for age-based vaccination recommendations, they are not designed to identify disease-based conditional recommendations. Thus, the pharmacist is fundamentally responsible for knowing who should receive the vaccine.

The 9-valent HPV vaccine is no exemption. The current age-based recommendations from the CDC are that all children ages 11 to 12 years should receive two doses spaced 6 to 12 months apart. For children older than 14 years of age, 3 shots should be given over six months for women up to 26 years of age and men up to 21 years of age. But there is no substitute for talking to the patient when it comes to making recommendations for young men who have sex with men (especially those who identify as gay or bisexual), young adults who are transgender, and young adults with immunocompromising conditions, all of which extend the recommendation to receive the vaccine through age 26.7

The state immunization registries can be helpful for identifying patients who could potentially be eligible for vaccination. Pharmacists in many community settings are now able to use either a given state’s web portal, or a vendor-provided platform to directly search the state or municipal registry for a patient’s vaccine history. State registry immunization data reliability varies by state but is generally very good for children and adolescents. Pharmacists should be aware of limitations of their jurisdiction’s registry when it comes to completeness for adults. Pharmacists should also keep in mind that while the registries are useful tools for identifying age-based opportunities, they will not be helpful in identifying disease-based recommendations because they do not house diagnostic information. Immunization registries can be especially helpful at identifying patients who have started but not completed a vaccine series or regimen, such as HPV.

Overcoming Barriers to Vaccination

Healthcare is increasingly moving from a paternalistic model toward one of shared decision-making. When making healthcare decisions, patients may not rely as extensively on information from healthcare providers as they do on information found on the Internet.8 As such, patients will often have challenges associated with the uptake of any given vaccine that pharmacists should be prepared to address.

While a comprehensive overview of vaccination challenges and solutions is beyond the scope of this article, there are two important barriers worth noting:

The first barrier is related to preference for non-vaccination. Vaccine hesitancy is a real phenomenon that affects approximately 25% of the population, with a continuum between those that accept all vaccines with doubts, ranging to individuals with complete refusal, and a heterogeneous group that lies between those two extremes.9,10 Pharmacists should keep in mind that directly challenging vaccination beliefs is not the most effective way of addressing vaccine hesitancy; do not fight fire with fire. Patients will often become more entrenched in their beliefs when directly confronted with epidemiological facts.11 Research has shown that vaccine-hesitant individuals are more likely to respond to messaging that appeals to their sense of community and vaccine effectiveness.12 Invite patients to protect their loved ones, and stress that the benefits of the vaccine outweigh the risks.

The second barrier—and one of the most common reasons that patients decline an invitation to be vaccinated—is related to point of care expectations rather than vaccine concerns. Patients generally expect to leave a pharmacy quickly. Pharmacists should consider proactively mitigating those expectations by reaching out to patients in advance of their coming into the pharmacy. For example, if a pharmacist sees a prescription for a younger patient, that’s an opportunity to check the immunization registry for the 9-valent HPV vaccine series, then directly reach out to either the patient or the parent to invite them to reserve more time to receive the vaccine when they come in to pick up the prescription.

Closing Out the Series

The last opportunity for pharmacists to capture are those associated with initiated vaccine series. Vaccine series and regimens that are not completed are truly a waste. Vaccine series reminders represent one method of ensuring that patients who start a series see it through to the end. The 9-valent HPV vaccine is a great example of this. Using electronic calendar items, postcards, mailers, phone calls, text messages, emails, and the like have all proven effective in helping patients remember to complete a series, including HPV.13 Whichever modality makes the most sense for the pharmacy and the patient is the one that should be chosen.

Samuel Stolpe, PharmD, MPH, is vice president, private sector, for the Scientific Technologies Corporation.

References

- Stolpe SF. The race to improve adult vaccination rates in the information age. Pharm Times®. September 7, 2017. pharmacytimes.com/publications/issue/2017/immunizationsupplementaugust2017/the-race-to-improve-adult-vaccinationrates-in-the-information-age.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Genital HPV infection fact sheet. http://www.cdc.gov/std/HPV/HPV-factsheet-March-2014.pdf.

- Muñoz N, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S, et al; International Agency for Research on Cancer Multicenter Cervical Cancer Study Group. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:518—527.

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Biological agents. Volume 100 B: a review of human carcinogens. IARC Monographs Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012;100(Pt B):1—441.

- Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189:12—19.

- Serrano B, Alemany L, Tous S, et al. Potential impact of a nine-valent vaccine in human papillomavirus related cervical disease. Infect Agent Cancer. 2012;7:38. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-7-38.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HPV Vaccines: Vaccinating Your Preteen or Teen. https://www.cdc.gov/hpv/parents/vaccine.html. Accessed Feb 16, 2018.

- Weaver JB, Thompson NJ, Weaver SS, Hopkins GL. Healthcare non-adherence decisions and internet health information. Computers in Human Behavior. 2009;25(6):1373—1380. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2009.05.011.

- Dubé, E., et al. Vaccine hesitancy. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013 Aug;9(8):1763-73. doi: 10.4161/hv.24657.

- The SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015;33(34):4164-4165.

- Nyhan B, Reifler J, Richey S, Freed GL. Effective Messages in Vaccine Promotion: A Randomized Trial. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):835-842. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2365.

- Nyhan B, Reifler J, Richey S. The Role of Social Networks in Influenza Vaccine Attitudes and Intentions Among College Students in the Southeastern United States. J of Adoles Health. 2012;21(3):113-119.

- Rand CM, et al. Effects of Phone and Text Message Reminders on Completion of the Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Series. J of Adoles Health. 2017;60(1):113—119.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.011.

Articles in this issue

almost 8 years ago

The Path Ahead for the HPV Vaccinealmost 8 years ago

Making HPV Vaccination Affordable for Patientsalmost 8 years ago

Dialogue and Education: Engaging Young Adults on the HPV Vaccinealmost 8 years ago

Patient Communication Strategies for Boosting HPV Vaccination Coveragealmost 8 years ago

HPV Vaccination in Young Adults: Are We Doing Enough?almost 8 years ago

The 9-Valent HPV Recombinant Vaccine: An IntroductionNewsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.