What Will Happen With Infectious Diseases as Vaccinations Decline?

Key Takeaways

- Measles could become endemic in the U.S. within 25 years if current vaccination rates persist, with up to 1.3 million cases projected.

- A 10% decline in measles vaccination rates could lead to 11.1 million cases, while a 5% increase could reduce cases to 5800.

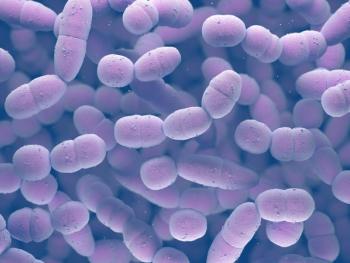

Experts forecast a potential resurgence of measles and other vaccine-preventable diseases in the U.S. due to declining vaccination rates.

Infectious disease specialists from Stanford University and Baylor College of Medicine published the results of

The model was based on childhood vaccination rates in 50 states and the District of Columbia from 2004 to 2023 and looked at how diseases could increase in prevalence over the next 25 years.

The only diseases in the model are those included in the standard childhood vaccination schedule: measles, rubella, poliomyelitis (polio), and diphtheria. Authors of the model looked at how incidents of the diseases and post-infection complications (such as polio-related paralysis, hospitalization and death) would rise or fall based on different rates of vaccinations over time, and how much time each disease would need to reestablish endemicity in the general population.

How Will Measles Affect the Population Under Changing Vaccination Rates?

The model used a latent period of 10 days for measles with a basic reproduction number (number of people who will become infected from one infected person) of 12.

According to the model, even the current levels of vaccination are insufficient to prevent measles for reaching endemic levels within the 25-year time frame used by the authors (83% of simulations, mean time 20.9 years). The US could see up to 1.3 million cases of measles in the next 25 years if current vaccination rates remain steady.

When authors input a 10% decline in vaccinations, that number rises nearly 10-fold to 11.1 million cases over 25 years; conversely, if vaccination rates rise by as little as 5%, the number of new measles cases will fall to 5800.

These numbers underscore the severity and contagion of measles, one of the world's most contagious diseases for which an effective vaccine (97%) is available and which was declared eradicated in the US in 2000.1

How will Polio, Diphtheria, and Rubella Fare?

The model showed that rubella, polio, and diphtheria are unlikely to become endemic in the next 25 years, even if childhood vaccination rates continue to fall.

This is due in large part to the shorter latency period and smaller basic reproduction number of these diseases compared to measles. Even though these diseases are infectious longer than measles, the actual rates of infection tend to be much smaller.

Reading The Fine Print

This assurance rings hollow, however, as forecasters "found that reductions in routine childhood vaccination will lead to reemergence and return to endemicity for all four infectious diseases under certain scenarios... [only] the timing and magnitude of case numbers and their critical population immunity threshold differed substantially by disease."1

The experts said at current vaccination levels, the US may see "sporadic outbreaks of varying size and duration" of rubella, diphtheria, and poliovirus. This prediction is reminiscent of how measles reemerged in the US beginning with an exposure at California's Diseyland in December 2014 that infected 147 people and spread internationally before that outbreak was declared closed in April 2015.2

The US saw its first new case of polio in July 2022 years when an unvaccinated adult returned to Rockland County, NY after traveling internationally. This was the first case of polio in the US since 1993.3

There are fewer than 10 new cases of rubella in the US each year.4

The last confirmed case of diphtheria in the US was reported in 1997.5

REFERENCES

1. Kiang M, Bubar K, Maldonado Y, et al. Modeling reemergence of vaccine-eliminated infectious diseases under declining vaccination in the US. JAMA. April 24, 2025. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.6495

2. Doll M, Correira J. Revisiting the 2014-15 Disneyland measles outbreak and its influence on pediatric vaccinations. PubMed. Sept. 8, 2021. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8828106/

3. Rai A, Uwishema O, Uweis L, et al. Polio Returns to the USA: An epidemiological alert. PubMed. Sept. 6, 2022. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9577438/

4. Impact of U.S. MMR Vaccination Program. CDC. Jan. 17, 2025. Accessed Sept. 10, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/rubella/vaccine-impact/index.html

5. Diphtheria Surveillance and Trends. CDC. May 12, 2025. Accessed Sept. 10, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/diphtheria/php/surveillance/index.html

Newsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.