Publication

Article

You Think You Know Aspirin? A Pharmacist’s Guide to Unlocking the Power of Aspirin

This article was sponsored by Bayer, maker of Bayer® Aspirin.

In 2020, heart disease and stroke resulted in a higher annual mortality (207.1 deaths per 100,000 people) than did cancer and chronic lower respiratory disease combined.1 Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) can lead to cardiovascular (CV) events such as myocardial infarction (MI).1 Risk factors for ASCVD include elevated lipoprotein(a) levels, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, high triglyceride levels, male sex, overweight, and obesity.1

Preventative measures are imperative for reducing the risk of ASCVD. Use of statins and other therapies intended to lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels is recommended for reducing ASCVD risk.1 However, more than 800,000 Americans still experience MI each year; these include 200,000 cases occurring in those who have had a prior MI. For patients who experience secondary events, antiplatelet therapy is imperative.1 Specifically, the 2019 American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease recommends aspirin use as an established secondary prevention measure to help prevent ASCVD.2 In the United States, Aspirin is indicated for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events.

Key Secondary Prevention Clinical Trials

The Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration

In 2009, investigators involved with the Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration meta-analysis compared the effects of long-term aspirin treatment versus a control treatment on CV events (including heart attack, stroke, and vascular death) and major bleeds based on randomized trial data.3 Their intention-to-treat comparisons considered initial events that occurred during the scheduled treatment period in all participants assigned to receive aspirin versus those in the control group, irrespective of concurrent treatment allocations.3

The meta-analysis of data from 16 secondary prevention trials compared the benefits and risks of long-term aspirin use versus those of the control.3 The results showed that compared with administration of the control, use of aspirin was associated with a 10% decrease in total mortality (rate ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.82-0.99; P = .02).3 Additionally, the use of aspirin reduced the risk of recurrent nonfatal heart attack by 31% and the risk of recurrent ischemic stroke by 22%.3 The analysis affirmed that aspirin use has the potential to reduce total mortality and to substantially reduce the risk of recurrent heart attack and ischemic stroke, supporting its favorable benefit-risk profile in secondary prevention.3

The ADAPTABLE Trial

The ADAPTABLE randomized clinical trial (NCT02697916) was conducted to determine whether use of an aspirin dosage of 81 or 325 mg/d was associated with a reduced risk of death, MI, and stroke in patients with existing ASCVD.4 As the primary end point, the investigators evaluated the time to a first occurrence of any event in the composite of death from any cause, hospitalization for MI, or hospitalization for stroke.4 Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to take 81 or 325 mg of OTC aspirin that they had purchased.4

In all, 15,076 patients enrolled in the pragmatic, open-label, patient-centered trial. There were 7540 patients in the 81-mg treatment group and 7536 patients in the 325-mg treatment group. At a median follow-up of approximately 26.2 months, an estimated 590 patients (7.28%) in the 81-mg group and 569 patients (7.51%) in the 325-mg group experienced death from any cause, hospitalization for MI, or hospitalization for stroke (HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.91-1.14).4 Hospitalization for major bleeding with an associated blood-product transfusion occurred in an estimated 53 patients (0.63%) in the 81-mg group and 44 patients (0.60%) in the 325-mg group (HR, 1.18; 95% CI, 0.79-1.77) at median follow-up.4

Dose switching was less frequent in the 81-mg group (7.1%) than in the 325-mg group (41.6%); the reasons for this difference were speculated to include patient preference, clinician practices, development of bruising and bleeding, and emergence of concurrent illness.4 Treatment was discontinued by 7.0% of patients in the 81-mg group and 11.1% of patients in the 325-mg group. Discontinuation was believed to be related to a perceived lack of effectiveness in both groups due to misinformation and public confusion.4 The effectiveness and safety outcomes did not differ significantly between the patient groups; however, those initially prescribed 81 mg were less likely to change doses or discontinue treatment than were those given 325 mg of aspirin to start.4

The investigators found that a lower aspirin dose (ie, 81 mg) appears to be as effective as a higher dose (ie, 325 mg) in preventing adverse CV events and poses a similar risk of bleeding.4 Moreover, patients prescribed the lower dose demonstrated better treatment adherence. These findings may impact how aspirin is prescribed to manage secondary ASCVD.4

Importance of Adherence to Aspirin Therapy

There is strong evidence for the effectiveness of aspirin in reducing the risk of secondary CV events; however, this medication has a suboptimal usage rate.3 According to the results of a cross-sectional analysis of pooled data from surveys conducted between 2013 and 2020 across 51 countries, self-reported aspirin use for secondary prevention in those with a history of CV disease was only 40.3% globally, with the range spanning from 16.6% in low-income countries to 65.0% in those with a high income.5

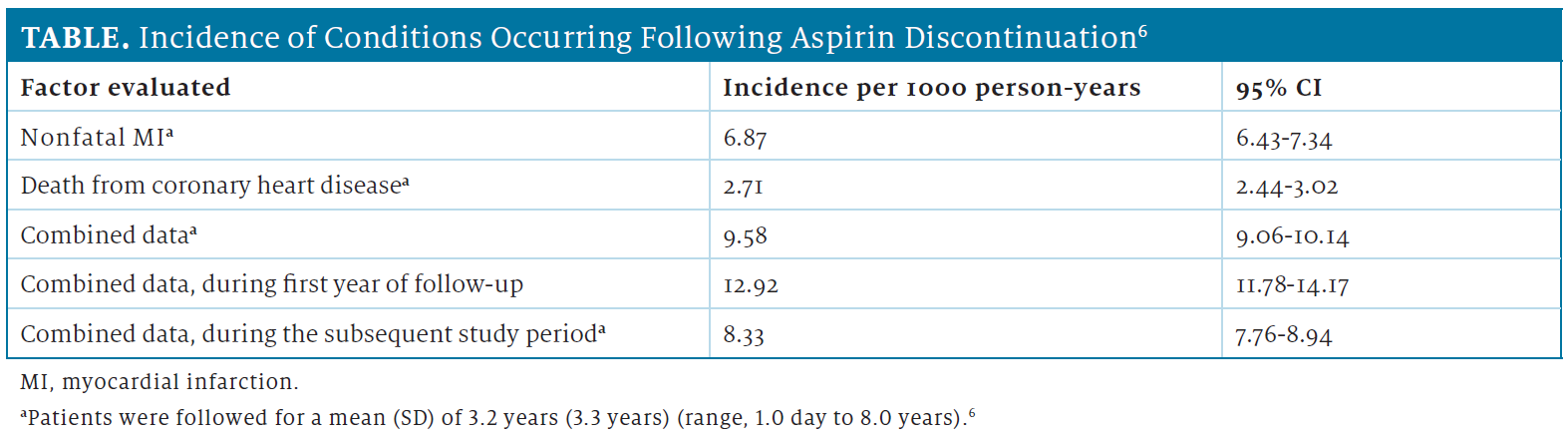

Of individuals who use aspirin, nearly 50% will discontinue therapy.6,7 In an assessment of the discontinuation of aspirin and its association with the risk of MI, the overall incidence of nonfatal MI was higher than was the overall incidence of death from coronary heart disease over a mean follow-up of 3.2 years.6 The combined incidence of nonfatal MI or death from coronary heart disease was higher during the first year of follow-up than during the subsequent study period (Table).6 These results were obtained from a retrospective analysis of information from a national-level database and included patients who received a new prescription for low-dose aspirin for the secondary prevention of CV or cerebrovascular events.6

Discontinuation of aspirin has been associated with increased mortality after acute coronary syndrome and a higher risk of ischemic and transient ischemic stroke within 15 days of stopping the medication among patients who previously experienced these events.6,8 Adherence to prescribed antiplatelet therapy, such as aspirin, is crucial for individuals who are at risk of experiencing secondary CV events.

Role of the Pharmacist

Promoting patient adherence to aspirin therapy to prevent secondary CV events is an essential role of pharmacists. Evidence from numerous studies, such as the Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration and ADAPTABLE trials, supports the beneficial effects of aspirin in reducing the risk of recurrent MI and ischemic stroke. Aspirin therapy adherence is critical, as discontinuation can have serious consequences, such as an increased risk of secondary CV events.

Pharmacists play an important role in addressing questions from both patients and providers. Through motivational interviewing and shared decision-making, pharmacists can explain the risks of discontinuing aspirin therapy and emphasize the benefits of long-term adherence, thereby empowering patients to have informed conversations with their doctors about their treatment plans.

REFERENCES

- Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2023 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2023;147:e93-e621. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001123

- Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596-e646. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

- Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration; Baigent C, Blackwell L, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1849-1860. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60503-1

- Jones WS, Mulder H, Wruck LM, et al; ADAPTABLE Team. Comparative effectiveness of aspirin dosing in cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(21):1981-1990. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2102137

- Yoo SGK, Chung GS, Bahendeka SK, et al. Aspirin for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease in 51 low-, middle-, and high-income countries. JAMA. 2023;330(8):715-724. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.12905

- Rodríguez LA, Cea-Soriano L, Martín-Merino E, Johansson S. Discontinuation of low dose aspirin and risk of myocardial infarction: case-control study in UK primary care. BMJ. 2011;343:d4094. doi:10.1136/bmj.d4094

- Sud A, Kline-Rogers EM, Eagle KA, et al. Adherence to medications by patients after acute coronary syndromes. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39(11):1792-1797. doi:10.1345/aph.1G249

- García Rodríguez LA, Cea Soriano L, Hill C, Johansson S. Increased risk of stroke after discontinuation of acetylsalicylic acid: a UK primary care study. Neurology. 2011;76(8):740-746. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31820d62b5

Newsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.