- October 2016 Diabetes

- Volume 82

- Issue 10

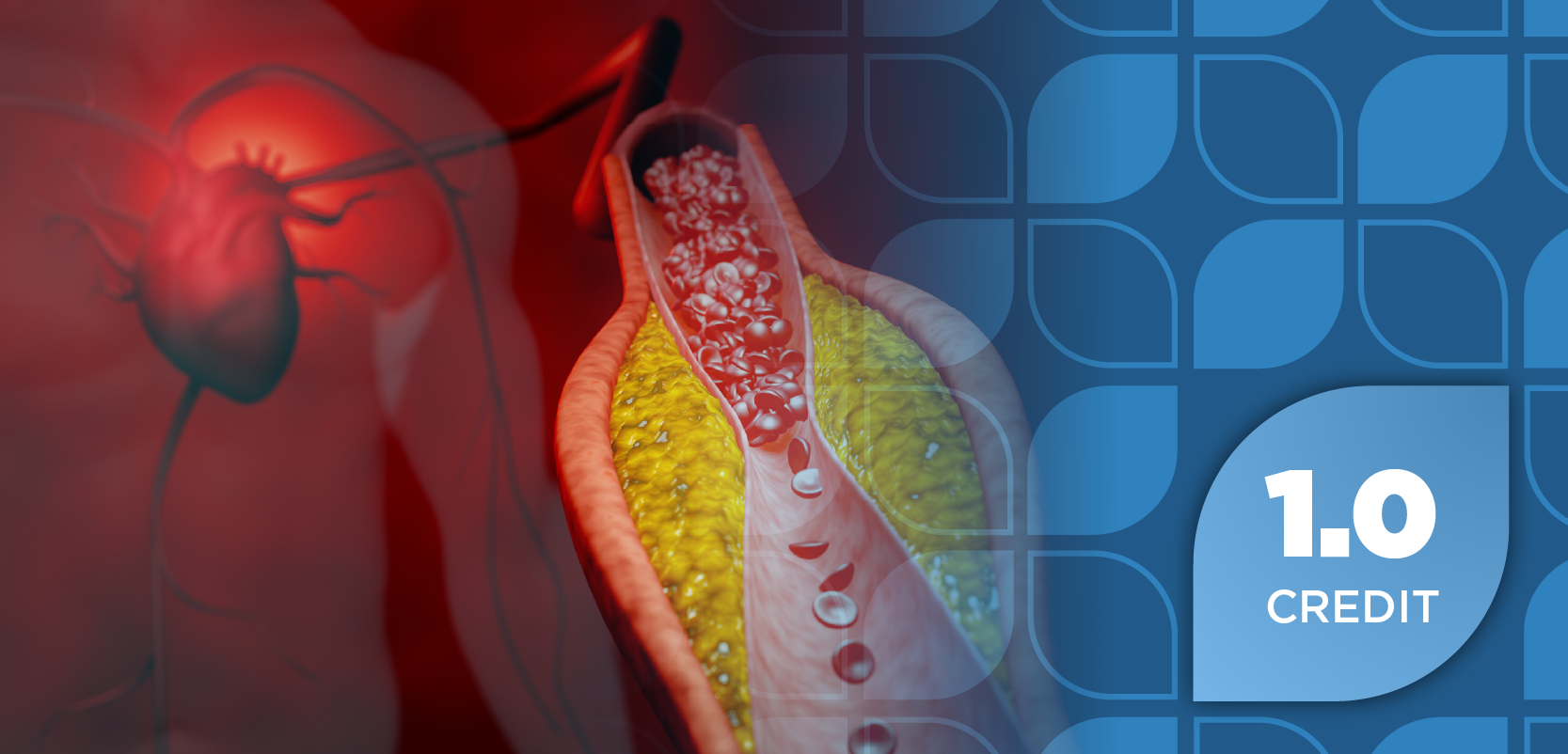

Cardiovascular Disease: Getting to the Heart of the Matter

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) (eg, coronary heart disease, stroke, peripheral artery disease) remains the leading cause of death among men and women.1,2 Although various CVD risk factors exist, most can be controlled or prevented through public health promotion, continuum of care, high-risk patient referral, and medication therapy management.3 Pharmacists worldwide are uniquely positioned to address most of these interventions for the primary prevention of CVD.4

The Framingham risk score and the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ACC/AHA ASCVD) risk estimator are being used to evaluate the 10-year risk of experiencing primary CVD.4,5 Both tools evaluate various risk factors (eg, age, gender, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol) and further risk for CVD. The ACC/AHA tool is currently being used to evaluate CVD risk by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).4 These tools are available through various apps, and pharmacists can ask their patients simple questions to evaluate their risk.4,5

After evaluating a patient’s CVD risk, a pharmacist can provide evidence-based nonpharmacotherapeutic, lifestyle, and/or pharmacotherapeutic recommendations. The USPSTF recommends nonpharmacotherapy, or lifestyle, modifications for all patients to lower their risk for primary CVD, especially for patients who are obese.4 These recommendations include smoking cessation, weight loss, increased physical activity, daily consumption of fruits and vegetables (eg, a Mediterranean diet), and low consumption of alcohol.4,6 These behavioral counseling interventions are purported to reduce total cholesterol levels by an average of 0.12 mmol/L (95% CI, 0.16-0.07), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels by 0.09 mmol/L (95% CI, 0.14-0.04), systolic blood pressure by 2.03 mm Hg (95% CI, 2.91-1.15), diastolic blood pressure by 1.38 mm Hg (95% CI, 1.92-0.83), diabetes incidence by 42% (relative risk [RR], 0.58; 95% CI, 0.37-0.89), and weight outcomes by a standardized mean difference of 0.25 (95% CI, 0.35-0.16).4,6 Table 14 lists the specific recommendations.

Various Cochrane reviews have suggested that interventions, such as consumption of green/black tea, nuts, omega-6 fatty acids, coenzyme Q10, selenium, and increased dietary fiber, have not been shown to improve or change primary prevention of CVD.7-12 Therefore, these complementary and alternative health interventions should be discouraged until further data suggest they have a consistent benefit in the primary prevention of CVD.

Aspirin is the key pharmacotherapeutic agent for the primary prevention of CVD. Currently, the USPSTF specifically recommends the use of low-dose aspirin (75-81 mg) for primary prevention of CVD in patients 50 years and older with the following health parameters4,13:

- At least a 10% 10-year CVD risk (using the ACC/AHA ASCVD risk calculator)

- Low risk for bleeding

- Life expectancy of at least 10 years

- Can be adherent to aspirin

These recommendations are based on a systematic review of 11 primary prevention trials of nearly 120,000 patients that suggested a 6% reduction in all-cause mortality (RR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.89-0.99) during follow-up of 5 to 10 years. However, there is insufficient evidence suggesting a primary prevention benefit for patients younger than 50 years or older than 70 years; therefore, these patients should receive aspirin for specific indications (eg, post myocardial infarction). Regarding safety, there was a 58% increase in the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding (RR, 1.58; 95% CI, 1.29-1.95). Hence, many clinicians suggest that the use of aspirin for primary prevention of CVD be individualized based on a comparison of the risk versus the potential benefit.4,13

In addition to aspirin, other medications are used for primary prevention of CVD (Table 24,14-16).4 The ACC/AHA ASCVD risk estimator may help determine whether statin therapy would be appropriate for managing dyslipidemia.

CONCLUSION

CVD continues to be the top cause of mortality among patients worldwide. Therefore, primary prevention of CVD is highly recommended for decreasing its incidence. Pharmacists are well positioned for disseminating interventions that can modify the risk factors for CVD, as they evaluate the risk among all their patients and make nonpharmacotherapeutic recommendations, such as increased physical activity, weight loss, consumption of fruits and vegetables, and low alcohol consumption. In moderate- to high-risk patients, aspirin remains the primary agent for preventing CVD. Other pharmacotherapeutic interventions include attaining blood pressure and diabetes treatment goals and adhering to statin therapy, if indicated.

Mohamed Jalloh, PharmD, is an associate professor in the Clinical Sciences Department at Touro University, California, and a community pharmacist for Walgreens.

References

- Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;61(4):1-117.

- Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006;367(9524):1747-1757.

- Final recommendation statement: healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: behavioral counseling. US Preventive Services Task Force website. uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/healthy-diet-and-physical-activity-counseling-adults-with-high-risk-of-cvd. Published May 2015. Accessed September 6, 2016.

- Tsuyuki RT, Al Hamarneh YN, Jones CA, Hemmelgarn BR. The effectiveness of pharmacist interventions on cardiovascular risk: the multicenter randomized controlled RxEACH Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(24):2846-2854. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.528.

- Vandvik PO, Lincoff AM, Gore JM, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(suppl 2):e637S-e68S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2306.

- Rees K, Hartley L, Flowers N, et al. ‘Mediterranean’ dietary pattern for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;12(8):CD009825. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009825.pub2.

- Hartley L, Flowers N, Holmes J, et al. Green and black tea for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;18(6):CD009934. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009934.pub2.

- Martin N, Germanò R, Hartley L, Adler AJ, Rees K. Nut consumption for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;28(9):CD011583. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011583.pub2.

- Al-Khudairy L, Hartley L, Clar C, Flowers N, Hooper L, Rees K. Omega 6 fatty acids for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;16(11):CD011094. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011094.pub2.

- Flowers N, Hartley L, Todkill D, Stranges S, Rees K. Co-enzyme Q10 supplementation for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(12):CD010405. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010405.pub2.

- Rees K, Hartley L, Day C, Flowers N, Clarke A, Stranges S. Selenium supplementation for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;31(1):CD009671. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009671.pub2.

- Hartley L, May MD, Loveman E, Colquitt JL, Rees K. Dietary fibre for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;7(1):CD011472. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011472.pub2.

- Mora S, Ames JM, Manson JE. Low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: shared decision making in clinical practice. JAMA. 2016;316(7):709-710. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8362.

- James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427.

- Standards of medical care in diabetes-2016. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(suppl 1):S13-S22.

- Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, et al; American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2889-2934.

Articles in this issue

about 9 years ago

Can You Read These Rxs? (October 2016)about 9 years ago

Case Studies (October 2016)about 9 years ago

Pet Peeves (October 2016)about 9 years ago

Generic Product News (October 2016)about 9 years ago

Change Together for the Betterabout 9 years ago

Educational Pharmacogenetics Resources for Pharmacistsabout 9 years ago

Diabetes Prevalence Has Nearly Quadrupled Since 1980about 9 years ago

Metformin Still Underused in Patients with Type 2 DiabetesNewsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.